Shimmering Salmon: Learning Balance

- Dec 3, 2021

- 8 min read

Updated: Apr 2, 2023

November 2021

In late fall, the main run of the shimmering salmon here in the Canadian Pacific Northwest is almost over. The salmon began arriving in our harbour in late summer, which is when we see sea lions and orcas appear more frequently too. Different salmon species—the chinook, coho, sockeye, pink and chum—make their way up streams and rivers at different times and places, depending on the location of their final spawning destination. In mainland British Columbia, sockeye go up first, as some of them have to travel more than 1000 kms inland. Here on Vancouver Island, chinook, chum, and coho return to their natal rivers and creeks. The salmon mill about in the estuaries, adapting to fresh water again and waiting for the fall rains, so water levels rise enough to move up waterways.

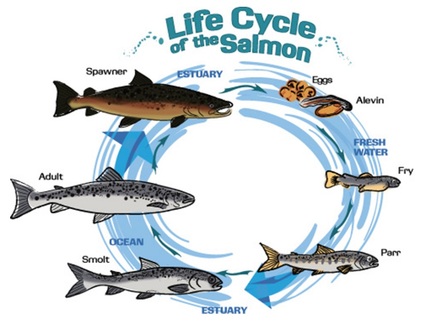

As a keystone species in this ecosystem, their lifecycles are truly astounding! Take the Chinook, the largest of the salmon, as one example. Eggs laid in the fall will develop slowly in the cold water until they hatch as alevins, with a yolk sac attached for their food, staying under cover of gravel. When the sacs disappear, they are ready to join the

water above, as fry. The Chinook fry move downstream to estuaries where they transform from freshwater to salt water fish, becoming silvery smolts.

From all the watersheds, including the majestic rivers of the Fraser, Skeena, Nass, Stikine and Taku, they move down complicated pathways to the ocean. There they spend another two to four years on circular journeys, between winter and summer feeding grounds, sometimes as far away as Japan. Some salmon primarily eat krill which gives their flesh a reddish colour. Once they are three to five years old, they begin their homeward migration.

Along the way they will be caught by marine animals, birds, commercial and recreational fisherfolk, and Indigenous groups. Of the 4000 chinook eggs laid by one female, likely only 4 adult fish return to their home river.

Many species turn the bright colours of spawning salmon; some develop the humped backs or hooked jaws of fully mature fish. All stop eating as they enter freshwater. Now all of their bodies’ energy goes into maturing their reproductive organs for mating, right down to the proteins in the fish scales themselves.

Witnessing their journey up streams and rivers is awe-inspiring. They are powerful fish able to jump up to 2 metres (6.5 ft) and more, leaping over

waterfalls, rapids, rock fall, logs and low dams. They move against fast currents and large volumes of water, with the onset of the rainy season.

The sheer power of their determination to fulfill their reproductive destiny instils humility…you can imagine how tired they are, hiding in pools to regain their energy to move further upstream. Forebears talk about being able to walk across the stream on their backs, in terms of sheer numbers.

Then, upon arrival to their birthplace, males vie for spawning females, chasing each other, using their hook noses called kypes to damage their rivals, demanding even more of their energy.

As they move up the stream, the eggs and milt they carry is maturing. They wait to lay until they are fully ripe. When ready, the female turns on her side and uses her large tail fin to dig a hollow in a gravel bed called a redd, usually a quieter place in the river or stream. She may lay thousands of eggs in several redds, dispersing them to ensure the best chance of survival. Within minutes of releasing the eggs, the male releases his sperm or milt over the eggs, fertilizing them. Sometimes, several males will fertilize the eggs, another insurance policy of the wild.

The females may spend their remaining days close to the eggs, but, with their role complete and their spent bodies, their inevitable death is close at hand. They develop white patches, lose their coloration, and become progressively weaker over days or weeks, until they die.

It was unnerving the first time I saw salmon bodies scattered all over the creek edges. It was like visiting a very large morgue. The smell was overpowering. In one location, volunteers dredged out wider beds of a creek, part of salmon habitat restoration.

They created more areas with rock falls, fallen logs, tree branches, and gravel to encourage spawning. On one visit meandering down this creek trail and shoreline, we saw the bodies of salmon everywhere in the forest.

Eagles and bears snag living or dead salmon first, from the quiet pools. One time, a mother bear treed her cubs 6 m (20 feet) up in a cedar while she fished. Male bears seem to come down to the streams dawn and dusk…and drag the carcasses far up into the forest, for their feast. Bears prefer the fattier parts of the salmon, the eggs, brain and skin, sometimes leaving the rest of the fish for wolves, ravens, crows, gulls, foxes, racoons, mink, and many others.

In early 2000, Equinox magazine published an article by Nancy Barron called “Salmon Trees”, revealing that salmon bodies discarded around streams perform a vital function. These imported stores of nitrogen find their way into the surrounding ecosystem and into the trees… a marine-to-land nutrient transfer of vast proportions. The salmon literally feed the trees! Further, salmon bodies decomposing in the water, feed the small microorganisms that will in turn feed their young salmon fry, as they emerge from the redds.

In a reciprocal relation, the trees support the salmon. They shade the streams keeping them cool enough for this cold water species who do not do well over 18 C (65 F) degrees, a problem in a climate warming world. The trees reduce the effects of flooding by soaking up the rain like a giant sponge and slowly releasing it to the watershed. Fallen trees provide protection and little pools creating nursery conditions favorable for salmon eggs. The intricacy of this beautiful dance is just one of the wonders of this beautiful Earth.

For these reasons, salmon have always been sacred to Indigenous people in both coastal and inland regions. The Tulalip of Puget Sound (Washington state) consider themselves descended from the salmon.

The ancient salmon saw the people walking on land. Some of them asked their grandfather to give them human form. He did, with the agreement that the salmon nation will take care of the human nation, if the human nation cares for the salmon.

Thus, the seasonal cycles of most tribal peoples up and down the coast are shaped by the movement of salmon. Several tribal groups, including where I live, are known as “people of the salmon,” essential to every part of their way of life. In fall, they traditionally welcome back the salmon ceremonially, with drum, song, and prayer. They ritually give their gratitude to the ones who die to give them life.

However, seeing this much death in the forest at once gives me pause: what are the salmon and salmon trees teaching us? I believe the lesson each fall is about the importance of balancing life and death. It is about making our lives worthy but also dying well, so that both our living and dying feeds future generations, related or not.

Many argue that Western society is afraid of death. Since the Enlightenment, the focus on change and continual progress means that we choose to focus on growth, even designing an economic system of continual growth. We have ignored decay, dying, and death. We go out of our way to distance ourselves from death. And yet, every October and November, we see the decay and withering all around us in the natural world. The salmon, spent after performing their exhaustive ritual of reproduction, move into a dying process without a fight. Yet, their contribution does not end with their death.

This cyclicality of seasons and generations has been lost on a civilization interested in a linear progression ever upward. As Gustavo Esteva and Madhu Suri Prakash describe in Grassroots Post-Modernism: Remaking the soil of cultures, we have been dumbed down in the art of dying and death. Through urbanization as well as the professionalization of healthcare, the medicalization of dying, and the funeral industry, we have lost the hands-on knowledge of how to assist the dying and their families, how to handle a body, and how the communal and cultural rituals at each stage give meaning to dying. They argue we need to regenerate these “non-modern arts of living and dying” in all their varied beauty.

Palliative psychologist Stephen Jenkinson, in Die Wise, calls our society death-phobic. He and others argue we have lost the wisdom regarding how to die well. He says most people who are dying do not acknowledge they are dying, hoping for the silver bullet or off chance. Family focus on physical symptoms, the tragedy of "bad news," and the time left, rather than facing death as a natural part of living, with rituals to guide each step toward death. This should include grieving during the dying process, rather than remaining stoic during dying. Too often grief is hidden, either the dying from family or the family from the dying. In fact, stoicism is considered dignity and silence is respect, rather than emotional deadening. At the end, to be as comfortable as possible, drugs are given so that the process feels gentler. In sum, Jenkinson calls it “cope, hope, and dope.”

Western society believes in mastery, and in this case we are mastering death just as we master the challenges of daily living or the big troubles we face. We “battle” illness and dying, thereby proving we are masters of our destinies, part of the progress narrative. Ernest Becker in The Denial of Death argues Western society develops hero stories as one pathway to “victory over death”…part of the linearity of the Judeo-Christian heritage. But perhaps there are parts of this journey that we need to rethink.

Both Becker and Jenkinson suggest that dying wise comes from practicing dying. I had the unique privilege to work with a spiritual teacher who gave us the opportunity to simulate dying and face our own deaths. What was so remarkable in this process was the calmness one feels in facing one’s death. But even more remarkable was how much dying is vital for providing meaning for living. As Sam Keen (in Becker) suggests, it is this voluntary consciousness of death that can take us past fear and despair, into renewed vitality for living.

What has been lost in Western society is the balance between living and dying. Living and dying are in relation; you do not know one fully without the other. Just as the salmon heroically move up the rivers and streams to their birth places, so we come full circle to where we entered an embodied, Earthly life. Through this portal, we are brought into life and through this portal, we will leave this life. It is this relation between the two that brings such deep meaning.

This circular understanding of life and death also teaches that our lives are food for the next generations and layers of existence.

What might it look like to restore rituals to accompany dying and death? I have known people who asked me for guidance, truly at a loss. What might it look like embracing this time, with great respect for the final aspect of life, alongside feelings of deep loss and sorrow? Those who are left behind move from death to funeral planning...then the grievers are left on their own. In sum, we bring a scientific rationalism and efficiency to what is a deep spiritual experience.

Malidoma Somé shares the ancient healing wisdom of Africa. He suggests, if possible, that the dying be assisted in working through their layers of Earthly experience, bringing closure, given beautiful last experiences of the senses, offered guidance for moving out of the embodied form, and then watchers keep vigil during the transition time. Perhaps it is time to ritualize this once again, so that this experience is life-giving…for the dying who will take on another form and for the family who slowly release the bodily experience of their loved one. Death is not an end but a transition, as the salmon lifecycle evokes.

Ritual can create a safe space for mourning and meaning-making. Somé describes wailers catalyzing the tears of family, music and songs/chants creating a safe mourning space, storytelling of friendships, gifting the newly deceased, sharing food among the living, and the power of communal grieving as a gift of love forging a pathway for the departing. Kevin Toolis (The Guardian, 2017 and My Father's Wake) says, this is what the Irish (and many other Peoples) still get right in their wakes. Such ritualizing feeds souls, which the modernization and professionalization of death no longer does. It helps bring back a cosmic significance to our individual human lives, within the flow of living and dying that is the Great Story of Earth and humanity.

Thanks to Howard Hsu for the Tulalip traditional story (Nexus Media). Thanks to Marvin Oliver for his print Spawning Salmon, www.marvinoliver.com and www.alaskaeaglearts.com.

Comments