Honouring our Ancestors: Blessings and Burdens

- Nov 14, 2022

- 7 min read

Updated: Apr 2, 2023

For many cultures, the ending of summer with its denouement in autumn, and the beginning of winter is a highly significant time. For the Celts, it has been Samhaim (SOW’en)—the ending of one year and the beginning of a new year, November 1. The harvest was over – the barns and food larders were full and/or the fattened animals were brought in from their summering pastures and some taken, so that their meat could be prepared for winter eating as well as for this seasonal festival. Moving into the darker part of the year, this festival had numerous aspects of which one was the honouring of ancestors. It was a time when the earthly world and spirit world were understood to overlap, enabling communication between the worlds, says Celtic researcher Caitlan Matthews.

With European colonization and the spread of Christianity, this practice was demonized particularly during the Inquisition, considered ancestor “worship” and thus idolatry (worshipping as if they were a god), detracting from the one Christian God. In colonial anthropology with its notion of cultures developing on a linear, hierarchical trajectory, such practices were considered to be “primitivism,” early forms of human religion in contrast to religion in a “civilized” society. Modernism, with its focus on the future, has led to a Great Forgetting, where remembering genealogies and family histories as well as living consciously for posterity is irrelevant. This is unfortunate, says professor of religion and ritual, Catherine Bell, for herein lies many cultural misunderstandings and profound losses. It led to a denigration of some very meaningful practices around the world, whose restoration can contribute to a rebuilding of cultural sustainability and depth.

It is fair to say that all human cultures respect their dead with complex, ritualized processes accompanying dying, death, and some form of resting place for the body, bones or ashes. Desecrating these special resting places is often considered a legal crime as well as offensive cultural violation. Once funerary rites are completed, family members may engage in small personal remembrances on anniversaries, such as lighting a candle or incense, offering prayers, and laying flowers or other gifts and remembrances, often at the burial site. Communal honouring of ancestors, however, has taken a cornucopia of shapes over the modern era.

The Roman Christian church designated All Saint’s Day (November 1) for honouring those who had been beatified as saints and All Soul’s Day (November 2) for honouring all those departed faithful.

The Eastern Orthodox church celebrates this in the spring. Protestants, with their broadened theory of “the sainthood of all believers,” commemorated all the dead, and sometimes the living faithful/saints too, on All Saint’s Day. It remains a public holiday or “feast day” with special religious services in many places.

In some places, such as the Day of the Dead in Mexico, syncretic practices exist, in this case blending Indigenous traditions with medieval Christian traditions to pay respects to the dead. They are offered gifts and food on a decorated altar or shrine (at home, in public places, or gravesites), conveying that the dead have not been forgotten.

In other traditions, Mahalaya is a Hindu festival paying respect to departed ancestors and honoring Goddess Durga, in the fall. Muslims observe the Thursday of the Dead in spring. The Chinese Qingming Festival (Tomb Sweeping Day or Ancestor’s Day) also occurs close to the Spring Equinox, involving ritual offerings at the graveside, such as burning paper gifts for the departed. The Japanese Obon festival in early fall also believes that this is a time of family reunion where lanterns guide the spirits home for a visit. It has also become also a time to remember those fallen in wars.

Ancestors is a very large and complex topic, not only because there are many definitions of ancestors and kinds of ancestors, but also the sheer diversity of beliefs and practices surrounding ancestors. This month, however, we can focus specifically on family or blood ancestors.

It is an especially good time to ponder our ancestral blessings as well as our ancestral burdens.

If you are not very familiar with your family history, I encourage you this month to explore your family genealogy, naming at least 7 generations if you can, along with the historical times in which they lived. This can include blood, half kin, adopted, foster, and chosen, dependent on your family reality. Collect as many stories as you can. In these ways, we become Rememberers. We engage in a remembering of the Big Story of our family — the overall story, bigger context, and specific realities that they lived. It is a remembering of your family’s part in the Big Story of humanity, understanding the themes, patterns, and experiences that bind all of humanity. The struggles of human nature are perennial, but so is the beauty that each family and culture contributes. Taking it a step further, your familial Big Story can be told orally or in writing to multiple generations in your family, so it is not forgotten, an important task of cultural restoration (see January 2019, January and September 2020 blogs).

As you do this story gathering work, the patterns of blessings and burdens in your ancestral lineage will emerge. Too often, especially with our more recent dead, we tend to focus on the hurts. But it is very important that we more consciously stand on the lineage of our ancestral blessings – the strengths, traits, abilities, and other gifts that have been passed onto us through our ancestors. In exploring my family history, for instance, I can see some of the gifts that commonly express themselves over many generations in my family…as spiritual leaders, educators, agriculturalists (farming/gardening), art and design, metal work, and technology innovation.

One can also more deliberately choose to stand on their rich cultural/multicultural history as well as familial history. The blending of specific cultures has created precious new peoples and a joining of gifts. This is one time of the year when we can offer our thanks to all our ancestors for the sum of the gifts they have passed on. Rather than just living in one’s own generation, understanding our gifts across the thread of multiple generational relations enhances the meaning and dignity in our lives as well as the depth at which we live. We come to understand what might be asked of us, as descendants, in this complex time.

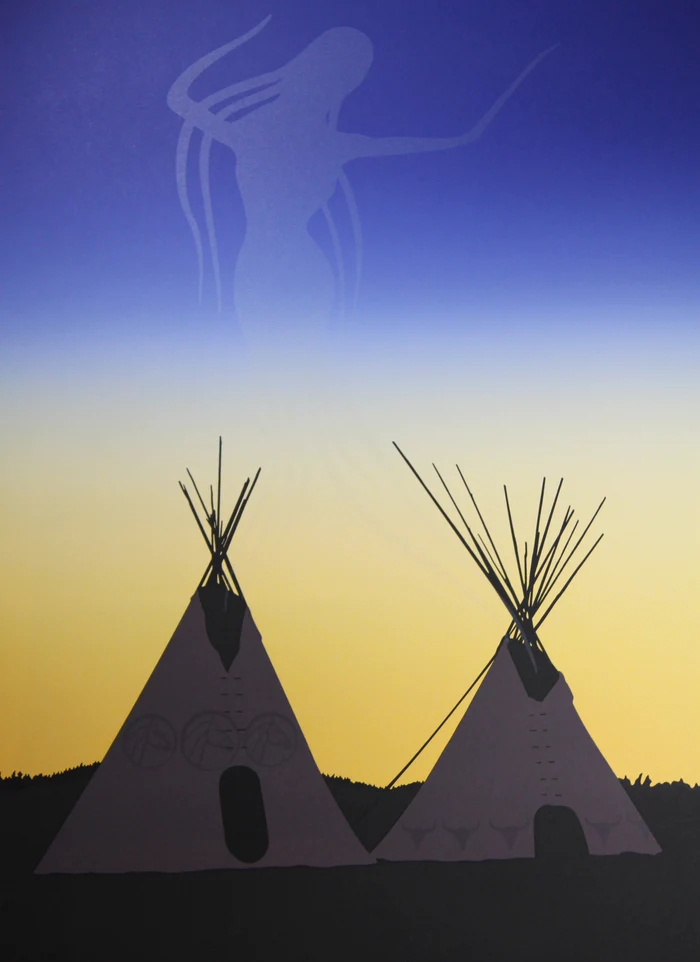

As many spiritual traditions believe, once the body dies, something continues. Psychotherapist and ritualist Dr. Daniel Foor suggests that Indigenous understandings are typically that the dead are still alive but in a spirit form and that the spirit world interacts with the earth world. This coheres with some of the New Science that intelligent consciousness pervades the cosmos. As Roy Henry Vickers (of Tsimshian, Haida and Heiltsuk ancestry in what is now British Columbia, Canada) portrays, some ancestors are always watching over us, helping us.

For our loved ones who have passed, we can take a day to honour them ritually (see December 2018 blog). As Foor says, when the dead are spoken to lovingly and given heartfelt offerings such as food, flowers, and drink, this is a beautiful time when they may come near briefly to be nourished and receive this active honouring, rather than existing forgotten.

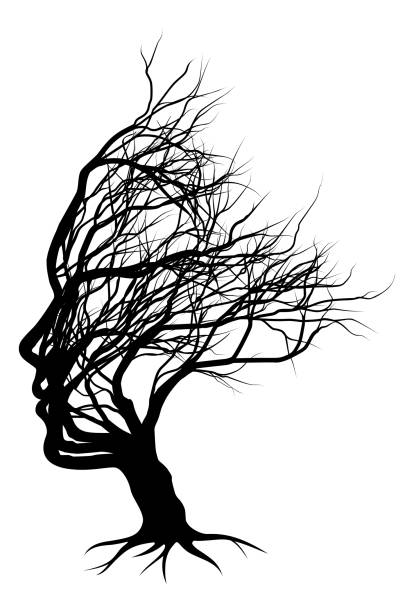

While it is accepted that we carry our family heritage genetically in body and traits, new epigenetic research goes much deeper. Not only can thought forms and behaviour habits be passed onto to us, but trauma can also create chemical markings on genes which are then transmitted across generations. For instance, all families have been touched at some time by the realities of famine, poverty, invasion, oppression, war, persecution, displacement, and other forms of collective suffering, such as slavery and attempted genocide. This pain can be manifested at the emotional, physical, and psychic levels, often operating unconsciously and silently. It can be the underlying basis for physical illness as well as psychological distress, showing up similarly across generations. It can also show up in belief systems that are debilitating for descendants, even though they meant survival for past generations. These can form some of our ancestral burdens and wounds.

Trauma such as this will grow across the generations unless it is acknowledged, and a process of healing undertaken. Sometimes, our role is just to express the grief of generations past…who could not, given the circumstances they were in. In this historical moment, our collective human task is to begin assisting in the healing and releasing of longstanding ancestral wounds, from a violent human history, so that they do not weigh down our personal, familial, as well as collective human history. From this, a fresh chapter in your family story can start. This is hard but worthy work … which may take a lifetime.

In working with a group of ethnocultural leaders from their immigrant and refugee communities, we probed our family stories for several years, examined the stories of major disruption such as Empire (colonization), war, and migration that have deeply marked families with suffering and trauma. We also dug for elements of cultural wealth and the blessings carried in our lineages. Then, among other healing processes, we wrote two letters, one a gratitude letter to the strong and healthy ancestors, thanking them for their blessings. The other was a reconciliation letter, sharing one’s understanding of the trials and suffering of an ancestor or group of ancestors. We each constructed a small raft, decorated it, and laid our letter of reconciliation upon it…letting it sail away on the river, releasing these burdens. We buried the gratitude letter amongst the roots of new planted trees, conveying that we are standing on and being fed by the “roots” of our ancestors.

As Matthews also says, it is at this time of the year that we have an opportunity to make peace with some of the departed. As I experienced, even at funerals/celebrations of life, new perspectives about your newly departed one emerge. Sometimes, taking a moment to express new understandings we did not have when they were alive can be helpful, perhaps moving a step closer to deeper understanding or even reconciliation. At the very least, we can speak truth…lovingly…and offer acknowledgement of the pain they carried. If one is ready, offering personal forgiveness can release the burden we may be carrying.

In slowing down and offering our thanks and gifts to our ancestors and departed ones, we can sink our roots more deeply into our positive inheritance and our long lineage of ancestral relations. We can also stand more consciously in the power of these gifts…standing on the shoulders of our healthy ancestors who were able to develop these gifts during their lifetimes. We can learn ways to make goodness out of hardship and learn the resilience our ancestors had during difficult times. We can move toward a healing of past troubled times and begin a healthier era. We can move through life with a deeper sense of belonging, identity, and peace we would not otherwise have.

Comments